Eric-Paul Riege: iiZiiT [3]: RIEGE Jewelry + Supply

January 31–March 29, 2025

Opening Friday, January 31, 2025, 6-8pm

Through a multilayered presentation of sculpture, installation, and video, iiZiiT [3]: RIEGE Jewelry + Supply examines the legacy of American Southwest pawn shops and trading posts, often encountered by Eric-Paul Riege in his home of Na’nízhoozhí (Gallup, New Mexico). While significant to Native art markets and livelihoods, historical pawn shops and trading posts—largely established by early European colonizers—facilitated centuries of unethical trading practices between settlers and Indigenous peoples. Today, modern trading posts continue to buy and sell Native goods, often catering to tourists and offering items disconnected from their original contexts and creators. By referencing the traditional trading post, Riege’s new site-specific presentation grapples with presumed notions of cultural authenticity and agency in the marketplace economy of Native goods.

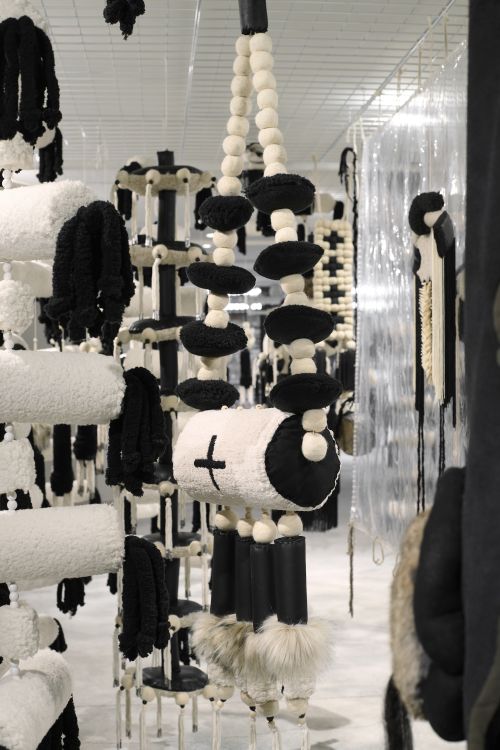

Riege’s hanging sculptures reference the jewelry worn by “Holy People”: giants from Diné tradition who roamed the Earth before humans. Titled jaatloh4Ye’iitsoh, or Earrings for the Big Gods, the monumental woven earrings and necklaces celebrate Riege’s matrilineal heritage of weavers, especially the protective deity Na’ashjé’ii Asdzáá (Spider Woman) who introduced early Diné people to the art of weaving. As one of Riege’s grandmothers taught him, wearing jewelry is thought to amplify the senses: earrings can hear what we miss and necklaces placed close to the heart help us feel emotions more deeply. Riege similarly considers his practice through the framework of beading and jewelry-making: much in the way that precious beads are continuously restrung onto necklaces, Riege’s felted beads are a mix of new and old materials which exist across a lineage of projects. The acts of spinning wool and weaving, for Riege, memorialize the changes and journeys that wool undertakes, having its own animacy and aura. Riege’s soft sculptures combine natural and synthetic materials—from genuine horse hair, sheep shearling, and wool hand-spun by Riege to synthetic dyed hair extensions and faux fur—creating textural contrasts while simultaneously dancing on the line of “real” versus “fake.”

Two large felted octagonal structures in the center of the room, called a hooghan, are reminiscent of Diné homes and welcome visitors into the space. Here in New York, far from Riege’s hometown, the hooghan enable him to recreate and share a sense of home, inviting visitors to walk into, between, and around their felted walls. In doing so, Riege invites us to consider the complex dynamics of host and guest, insider and outsider, and how these relationships are negotiated both in public spaces and on unceded land. As the textile hangings and chandelier earrings gently sway in the space, Riege demonstrates their full activation through the video work at the end of the room. In the video—which serves as an ad for RIEGE Jewelry + Supply—the artist performs his “weaving dance” in which the textile sculptures are jingled, dropped, and moved in reverbbed and low hums, capturing their ambient and energetic movements.

Riege’s plastic weavings repurpose packing materials used by museums to ship his works, which not only provide protection in transit but also imbue them with a degree of preciousness, the same value attributed to Indigenous artifacts exhibited behind vitrine casings. Throughout the exhibition, Riege displays found or purchased Native regalia and jewelry sourced from various contemporary jewelry and trade shops in Gallup, referencing traditions of cultural adornment and self-fashioning. In these works, Reige highlights the beauty of the regalia while also emphasizing their isolation. Especially when displayed in homes and museums where they are stripped of their function and context, the presence of these items prompt questions around possession and appropriation.

The title of the exhibition, iiZiiT [3]: RIEGE Jewelry + Supply, refers to a double entendre commonly heard on the reservation where Riege lives—“is it?” or “for real?”—which poses the ontological question, “is it real?” Riffing on the counterfeit merchandise industry and material culture of Canal Street, where Canal Projects is located, the exhibition presents Riege’s nuanced readings of cultural authenticity, systems of exchange, and notions of value.

Eric-Paul Riege (b. 1994, Diné/Navajo) works across media with an emphasis on woven sculpture, installation, and performance. He celebrates the ancestral stories in weaving, language, and adornment passed down from his maternal family. As a descendent of this knowledge, Riege honors the Diné worldview of hózhó which encompasses the values of beauty, balance, and goodness in all things physical and spiritual. What results are sensorial projects built in homage to ceremony, cosmology, and craft.

Riege’s recent solo exhibitions include Hóló llUllUHIbI [duet], Hammer Museum, and Hóló—it xistz, ICA Miami. Recent group exhibitions include Ten Thousand Suns, The 24th Biennale of Sydney, Australia; The Land Carries Our Ancestors, National Gallery of Art, Washington DC; Indian Theatre: Native Performance and Self-Determination since 1969, Hessel Museum of Art, New York; What Water Knows, The Land Remembers, Toronto Biennial of Art; Prospect.5: Yesterday we said tomorrow, New Orleans Triennial; and Casa Tomada, SITElines Biennial, SITE Santa Fe.

He received his BFA in Studio Art and Ecology, with a minor in Navajo Language and Linguistics, from The University of New Mexico. Riege lives and works in his hometown Na’nízhoozhí (Gallup, New Mexico). Riege’s work is in the collections of the National Gallery of Art, Hammer Museum, ICA Miami, LACMA, Denver Art Museum, Montclair Art Museum, Forge Project, among others.

I am a maker and artist and language keeper working in woven sculpture, installation, wearable art, collage, sound, and durational performance. I honor the Diné (Navajo) worldview of hózhó which encompasses the values of beauty, balance, and goodness in all things physical and spiritual and

its bearing on everyday experience. My work is a celebration of ancestral knowledge passed down by my mothers family. I am a descendent of weavers and fiber artists extending back to Na’ashjé’ii Asdzáá (Spider Woman); a Holy Person who protects Diné peoples and taught us how to weave. I consider all that I do a form of weaving. When there is a warp there is a weft and a cross (+) happens and this cross is what I embody.

I was told by one of my grandmothers that we adorn our body with jewelry so our Holy People can find and follow us and that our jewelry is listening and feeling with us. I began making large textile earrings as totems of memory called jaatloh4Ye’iitsoh meaning “ear rope for the big gods/ monsters” which mimics and embellish the traditional looped form of stacked beads. My jewelry and weaving pieces also deal with economies and cultures of the marketplace, especially as related to authenticity and what is perceived as authentically Native American. The expectations around

value and spectatorship particularly in materiality and

presentation allows me to play with the precious and non-precious and the high and low.

My soft sculptures hang to create immersive installations of welcome that suggest a home or hooghan: the ceremonial place. These spaces are charged with the spirit and memories of the gifts I have been given to become spaces of refuge. The loom itself is technically the first home of a weaving so the walls of my installations are often comically large Navajo looms. Homes exist externally and internally, physically and figuratively and these homes welcome you to enter, look, and stay. It is our sanctuary to share.